When we or someone we love is dying, the mind sometimes responds in ways that don’t make sense to outsiders. I’ve seen a daughter insist that her mom was getting better, even as I watched her mom slip further away.

All the while, the daughter was planning a vacation for the two of them.

I once sat vigil for someone who was actively dying. My client was a difficult man, estranged from most of his family and friends. His husband swore the man was “deeply loved by everyone” and planned a funeral that very few would attend.

These moments can look like denial, misremembering, or fabrication. But often, what we’re seeing is something else entirely.

What is Magical Thinking?

Magical thinking is the unconscious belief that our thoughts, wishes, or symbolic actions can shape reality. Most of us do this as children. Who among us remembers saying, “Step on a crack, break your mother’s back”?

It returns in force during times of uncertainty. This is especially true when someone is approaching the end of life.

At its core, magical thinking is not irrational. It’s emotional logic. When control is slipping away, our minds often reach for something to hold on to. In whatever way it can.

Have you ever witnessed a dying person planning a vacation for next spring, even though they’ve already entered hospice? It may feel strange or even upsetting. But to the dying person, imagining a trip is a way to stay rooted in something joyful.

It’s not necessarily about literal belief; it’s about spiritual momentum. Planning a trip gives them a sense of normalcy. They’re able to talk about something other than their own decline. That kind of hope, even if it’s improbable, reduces fear and improves their mood.

Where’s the harm in that?

Magical Thinking in Caregivers

Loved ones, too, participate in magical thinking. I’ve seen it manifest itself in the stories they tell about the person who is dying. An absent father becomes “the most devoted dad in the world.” An isolated spouse is described as “everyone’s favorite.”

This sudden sainting of the dying is rarely about deception. It’s more about mercy. Loved ones honor the best version of the person in their final days. It helps them find a thread of peace in an otherwise painful goodbye.

The facts of the past don’t have to disappear, but the story the family chooses to tell softens the harsh reality of the moment.

Of course, to an outsider, magical thinking looks and sounds like avoidance. Sometimes family members push back.

“That’s not what the doctor said.”

“You know she isn’t going to make it.”

“Why are you pretending he was kind when he wasn’t?”

This urge to correct the record sometimes does more harm than good. At the end of life, emotional truths often matter more than literal ones.

Instead of confronting or correcting, we can ask: What need is this belief fulfilling? What comfort is this story offering?

Sometimes, magical thinking helps a caregiver keep going: “If I don’t fall apart, they won’t either.”

It gives a dying person the courage to face one more morning: “If I picture myself at my granddaughter’s wedding, I can last through the week.”

These aren't lies. They’re lifelines.

There’s even a kind of poetry to it. In a culture that prizes logic and control, magical thinking gets a bad rap. But at the end of life, the rules change. Time stretches. Memory softens. Stories shift to fit the heart.

As someone who believes in the power of telling the truth, I get that going along with it feels like delusion. But when someone is dying, they and their loved ones are sometimes filled with grief.

I can set aside reality for a moment and allow them this effective coping skill. It won’t kill me.

To do this with more empathy and less judgment, I remind myself that this is what grace looks like.

How to Practice Responding in Ways That Help

Again, I understand that being around someone who’s experiencing magical thinking can stir up discomfort. So many of us want everyone to “face reality.” But remember, whether you’re supporting a dying person or their loved ones, you don’t have to agree with them.

You also don’t have to correct them.

Simply honor what they need in that moment. Here are a few gentle ways to do that:

Use the Ring Theory

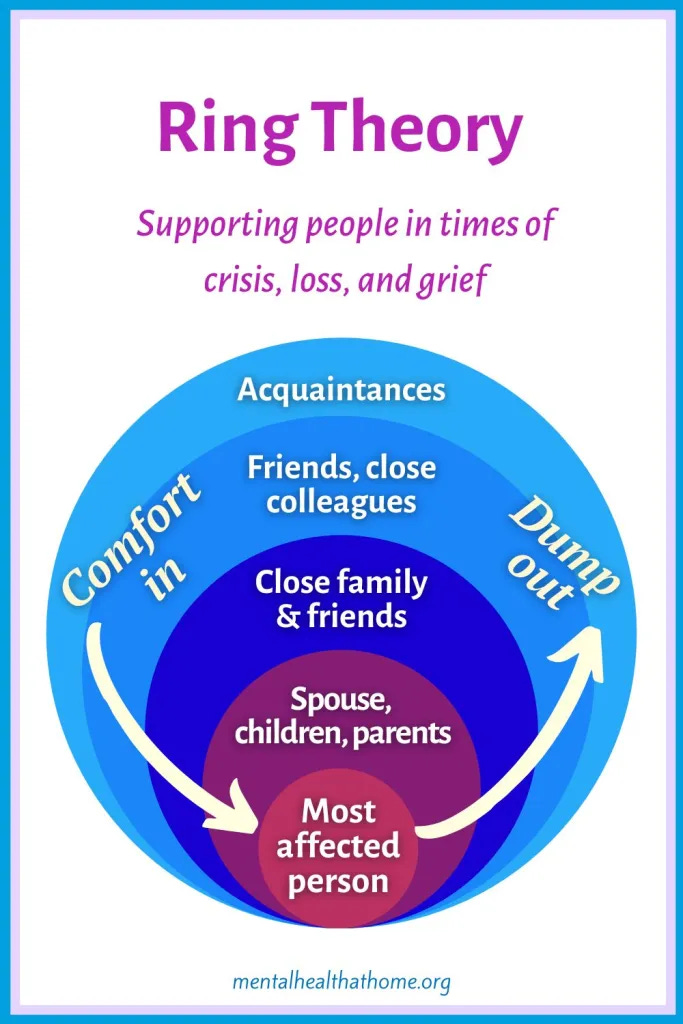

Created by psychologists Susan Silk and Barry Goldman, this model teaches us to “comfort in, dump out.” See the picture above.

There are a series of concentric circles: the person who is dying is in the center; their closest caregivers are the next ring out; friends and extended family follow.

If you are in an outer ring, your job is to offer comfort inward, to those closer to the crisis. Take your own fears or complaints outward to someone better positioned to receive them.

Don’t ask the grieving to manage your discomfort.

Be a Witness, Not a Referee

You don’t have to fact-check someone’s story. If they believe their loved one waited for the full moon to pass before dying, let it be.

Try phrases like: “That’s a beautiful thought,” or “Sounds like that meant something to you.”

You’re not endorsing the details. You’re honoring the meaning.

Let People Rewrite Their Story

If a caregiver begins talking about their mother as if she were a saint, even though you remember years of conflict, be the hush. (As my family would say…)

This is not the moment for the full historical record. Later, you can journal your thoughts or write a book. Allow caregivers their survival strategy and, for now, spend more time listening than speaking.

Stay Curious

When you hear something that surprises you, like plans for a future that won’t happen, try asking, “What’s drawing you to that idea?” or “Tell me more about what you imagine.”

That opens space for connection, rather than correction.

Respect What You Can’t Understand

Not everything at the end of life is explainable. Sometimes people see things we don’t. For example, I have clients say they’re ready to die, and yet they still hold on.

Some have fully planned their escape and then never take it. That doesn’t make them irrational. It makes them human.

Remember that magical thinking isn’t about pretending. It’s about preserving a sense of wholeness in a world that feels like it’s breaking apart. If we meet the moment with grace, we offer dying people and their loved ones something even more healing than truth: love that doesn’t need to be right.